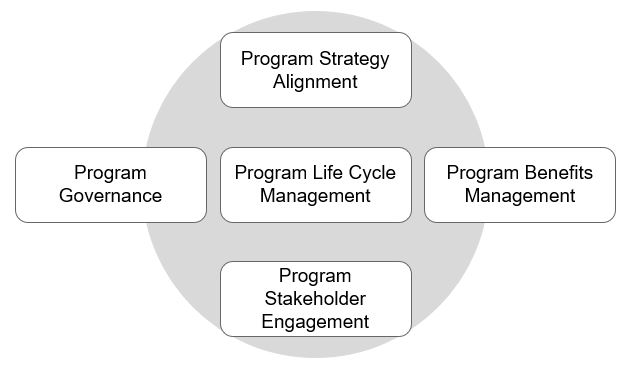

Program Management Performance Domains are complementary groupings of related areas of activity or function that uniquely characterize and differentiate the activities found in one performance domain from the others within the full scope of program management work.

1. Performance Domains Definition

1. Performance Domains Definition

Definitions of the Program Management Performance Domains are as follows:

- Program Strategy Alignment—Performance domain that identifies program outputs and outcomes to provide benefits aligned with the organization’s goals and objectives.

- Program Benefits Management—Performance domain that defines, creates, maximizes, and delivers the benefits provided by the program.

- Program Stakeholder Engagement—Performance domain that identifies and analyzes stakeholder needs and manages expectations and communications to foster stakeholder support.

- Program Governance—Performance domain that enables and performs program decision making, establishes practices to support the program, and maintains program oversight.

- Program Life Cycle Management—Performance domain that manages program activities required to facilitate effective program definition, program delivery, and program closure.

2. Performance Domain Interactions

As introduced previously and depicted in figure above, all five Program Management Performance Domains interact with each other throughout the course of the program.

When organizations pursue similar programs, the interactions among the performance domains are similar and often repetitive. All five domains interact with each other with varying degrees of intensity.

These domains are the areas in which program managers will spend their time while implementing the program.

The five domains reflect the higher level business functions that are essential aspects of the program manager’s role regardless of the size of the organization, industry or business focus, and/or geographic location.

3. Organizational strategy, portfolio management and program management linkage

Programs typically find their starting point during an organization’s strategic planning effort, where the full spectrum of the organization’s investments are evaluated, prioritized, and aligned with the organization’s operational strategy.

Programs are typically reviewed to ensure the program’s business case, charter, and benefits management plan reflect the current and most suitable profile of the intended outcomes.

A concept may be approved for a limited time with limited funding to develop a business case for further evaluation. The business case is then reviewed during the portfolio review process.

Programs may close when the benefits and objectives to be achieved by the program are no longer in alignment with the organization’s strategy or when measurements against the program’s KPIs reveal that the business case for the program is no longer viable.

4. Portfolio and Program Distinctions

To clarify the difference between these important organizational constructs, two aspects stand out: relatedness and time.

- Relatedness. In a program, the work included is interdependent such that achieving the full intended benefits is dependent on the delivery of all components in the scope of the program. In a portfolio, the work included is related in any way the portfolio owner chooses.

- Time. Another attribute that differentiates portfolios from programs is the element of time. Programs, like projects, are temporary and include the concept of time as an aspect of the work.

Though they may span multiple years or decades, programs are characterized by the existence of a clearly defined beginning, a future endpoint, and a set of outcomes and planned benefits that are to be achieved during the conduct of the program.

Portfolios, on the other hand, while being reviewed on a regular basis for decision making purposes, are not expected to be constrained to end on a specific date.

5. Program and Project Distinctions

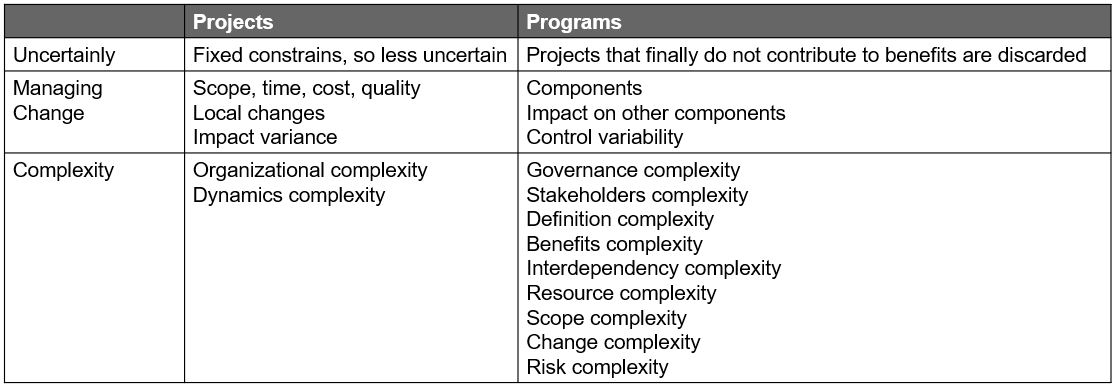

These fundamental differences are found in the way programs and projects are managed in response to uncertainty, change, and complexity.

Uncertainly

Uncertainty is especially high in the beginning of a program as the outcomes are not clear. In projects due to fixed constraints, the uncertainly is lower than in programs.

Changes external to the organizational environment also create uncertainty, which increases the uncertainty of managing programs. Within the context of the organization, however, individual projects may be considered to be more certain than programs.

As a project proceeds, its ability to deliver those outputs on time, on budget, and according to specification becomes more certain as a result of the progressive elaboration that removes uncertainty during the course of the project.

By contrast, a program may not have its entire scope, budget, or timeline determined upon preparation. This in turn can be addressed by the program’s ability to deal with uncertainty because programs can change the direction of projects, cancel projects, or start new projects to adapt to changing circumstances.

This ability creates uncertainty about the program’s direction and outcome.

Change

Program managers need to consider two different categories of change.

- Internal change refers to changes within the program.

- External change refers to the need to adapt the organization in order for it to be able to exploit the benefits created by the program.

Projects deal with change in terms of scope, time, cost, and quality. Programs should be better equipped to deal with change because they have the ability to change the direction of a component, cancel a component, or start a new component.

In both programs and projects, there should be a rationale that justifies that the advantages originating from a proposed change will outweigh potential drawbacks.

In programs, change management is a key activity, enabling stakeholders to carefully analyze the need for proposed change, the impact of change, and the approach or process for implementing and communicating change.

Complexity

The complexity of a program may be the result from a combination of factors.

- Governance complexity. Governance complexity results from the sponsor support for the program as well as the support of the related components’ sponsors, management structures, number of organizations involved and the decision making processes within the program.

- Stakeholder complexity. Stakeholder complexity arises from the differences in the needs and influence of stakeholders, which may be a burden to the program or in conflict with the benefits of the program.

- Definition complexity. Other aspects that the program manager should be cognizant of include benefits management and the potential competing interests of stakeholders.

- Benefits delivery complexity. Benefits delivery complexity focuses on benefits management,

- Inter-dependency complexity. Program managers need to deal with inter-dependency complexity.

The table below summarizes the key distinctions:

Programs strengthen and enforce inter-dependencies among components to ensure that the overall outcome of the program delivers the intended benefits. Inter-dependencies among components and other business entities should be clearly defined.

Good work.